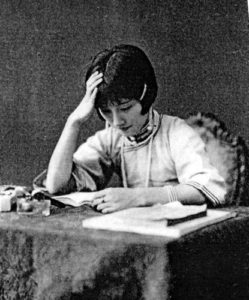

Xiu Wei writes from Malaysia. She was born in Klang, a small town where big, black crows fly amok. The crows have inspired her to (attempt to) fly amok as well. She aspires to acquire the gentle, happy disposition of an alpaca, and to be the best human she can possibly be.

Eggshells

The conjuring of one’s primary school memories usually gave Big People a fond feeling in their belly. “Those good old days,” one would say. “It was the happiest time of my life,” said another. Or: “I wish I could go back.” At least, this was what she observed. It happened with her brother, who was not really a Big Person per se, but he was two years closer to becoming one compared to her. She heard the same echoes from her mother, father, and relatives too. “Appreciate the time you have now at school,” the Aunty at the store would tell her. “You’re going to miss it when you’re older!”

But she wasn’t so sure about that. For this little girl, school was strange, to say the least. It was a time of such fixity that it often made her feel quite uncomfortable. I mean, even the categories of their age groups were called Standards. She was in afternoon class Standard 3, just one year before she turned 10, when she would become a morning upperclassman. The teachers’ words whipped their world into shape. Everyone had to wear uniforms, and she didn’t quite like the dark blue pinafore and white button-up blouse combo. The uniforms she wore were hand-me-downs outgrown by her mother’s friends. They were older, bigger than her, but still the uniforms fit rather snugly. They had always said that she was tall for her age. In fact, she was the tallest girl in class. She towered over even the boys – but she must stress that inside she always teetered rather daintily.

And that was why she was always a different shade of color compared to the other girls: her pinafore a little less blue, and her blouse just a little more gray. She had to wear a cloth belt too, and it cinched in her waist a tad too tightly. It had already been altered by her mom; she took out the hook and sewed it at the very far-most edge of the belt possible. And yet all that extra space was not enough for her – she would sheepishly, ashamedly, secretly undo the clasp of her belt during class when nobody was looking and breathe a little easier after that, hooking it back when they have to go for recess.

Everyone in class had a nickname, but you could not choose it. Her classmates called her Tsunami because of her very curly hair that stuck out in all directions like strong waves. Nobody knew who exactly came up with these nicknames, but they just appear out of thin air and cling onto you like goosebumps. Tsunami walked into class every day with a ponytail so tight that it raised her eyebrows 2 millimeters higher, and she wore a pair of big, black metal pins that clipped her bangs onto her scalp like a jail – she would always hope that this taming would make her seem less Tsunami-y, but the nickname never dropped. Shi Yi’s hair was jet-black, silky straight and soft, and yet, her nickname was Dove. Like the shampoo Dove and like the gentle white bird dove. Tsunami thought it was rather unfair. Why not call her Seaweed or Crow instead?

But still, all was tolerable because Tsunami had a window seat. There were 45 little boys and girls in class, and because she was the tallest, she sat at the back-most row by herself, right next to the window that overlooked the big rectangular school field (which was also right in front of the class dustbin). Tsunami was the only one in class who knew that if you leaned back against the wooden chair until it stood on two legs (exactly like how the teachers say you were not supposed to), and peer just across the missing panel of the folding glass window, you could catch a glimpse of it. There! At the eye-level of a tall 9-year-old girl, within the foliage of a thin tree, nestled a nest of tiny bird eggs. Quail eggs, grey and frail and speckled with brown. The tree housing the nest was shaped rather oddly, being sparse and spindly, and its branches extended towards Tsunami’s window like an outstretched palm as if it were offering her a gift. Tsunami took this as a sign that she was fated to watch over the eggs, and she would puff up with pride even though it made her belt constrict even tighter. Whenever Tsunami checked on the nest – discreetly of course, so nobody discovered it – she dared not look down. She dared not look down because the nest balancing on the two-story tall tree would suddenly seem so very far away from the ground, and the eggs would seem so very precious that it made her heart ache in a rather peculiar way. She didn’t lay them, she knew that of course, but those were her eggs all the same. They made her special.

It was class intermission time and Tsunami was performing her usual nest-checking before Ms. Fang, their homeroom teacher, entered the classroom. Ms. Fang was a very thin lady with big bulbous eyes that tended to glaze off halfway during class when she would drift into stories of her younger years. Everyone was rather fond of her, though she could get a bit too naggy at times. Tsunami thought Ms. Fang was alright except for the fact that she looked a little scary up close – her eyes always seemed to stare right into your insides. And Tsunami could never be sure what exactly Ms. Fang saw inside of her.

The eggs were alright as usual, peacefully residing in their nest, when they were suddenly seemingly seized by an invisible hand and began to shake in a frantic manner. Tsunami’s eyes opened as wide as Ms. Fang’s and she held her breath, afraid that the eggs would plummet onto the pavement below. Sticking her head out of the window hole with the missing panel, she forced herself to look down and quickly realized that this shaking was caused by an upperclassmen boy. He was almost bald with tanned skin, and his shirt was untucked into his pants (which was a sure bad sign). He also had the stupidest, biggest grin on his face as he shook the thin tree with both his arms, with all his might.

Tsunami’s heart beat so violently it was about to fly away from her ribcage. She had to do something.

“Hey, you!” she yelled after summoning all the courage that hid in her marrows. She rarely yelled.

The boy ignored her and continued shaking the tree in a demented manner.

“YOU! BOY!” Tsunami roared desperately.

He finally heard her.

“What?!” he said.

Tsunami knew the boy was shaking it because of the nest. So it was no use to tell him not to harm the eggs. Frantically, she thought about how to convince him to stop.

“If you keep shaking the tree, I’ll tell the teacher!” she threatened.

The boy sneered and jeered like an idiot. “Yeah right! You would already have if you could!”

Frustrated, Tsunami turned around. Ms. Fang wasn’t there yet. Tears started trickling out of her eyes like a leaky faucet.

“Hey,” Tsunami quickly stopped one of her classmates, Mei Fang, who was passing by after throwing pencil shavings in the dustbin behind class.

“Hey, Tsunami,” Mei Fang exclaimed in surprise. “Why are you crying?”

Tsunami pointed helplessly outside to the tree that was quaking in fright.

“There’s a boy shaking that tree.”

Mei Fang frowned.

“He’s just one of those naughty boys,” she said dismissively. “Don’t mind him.”

“No, no,” Tsunami said hurriedly. Mei Fang didn’t understand. She took a quick breath and decided to share her secret.

“There’s a nest in the tree.”

Mei Fang peered at where she was pointing and caught sight of the dainty eggs sitting on the tree, behaving so well despite the havoc being wrecked upon their home.

“Ohhhh,” Mei Fang exclaimed. She didn’t react as much as Tsunami had expected her to. “That boy is so naughty.”

“We need to stop him,” Tsunami said commandingly although she did not know what to do. She knew Mei Fang would not know what to do either. It was just simply unthinkable to run out of the classroom during class time; nobody did that. Especially not well-behaved little girls. And she couldn’t bear the thought of tearing her eyes away from those precious eggs. What if they fell while she was gone?

“I don’t think we can,” Mei Fang said gravely. Tsunami’s heart sank. Just at that moment, the steady click-clack-click of heeled footsteps clocked into their ears, and Mei Fang hastily patted Tsunami’s head before rushing back to her seat. “Don’t cry Tsunami,” she whispered compassionately. Ms. Fang entered the class.

“Atten-tion!” The class monitor commanded.

“Good morning, Ms. Fang,” All of them rose, droned, and bowed to the teacher.

“Sit down,” Ms. Fang said.

“Thank you tea-cher,” they droned again before sitting back down. Tsunami’s tears were still sliding down the curve of her cheeks.

The classroom was quiet now, stiflingly quiet, as they awaited Ms. Fang to announce what they were going to do that day. It is important to know that Tsunami was usually very good at keeping her sorrows in the drawers of her chest. They shut tight when she breathed in deeply and opened when she breathed out, during which some sorrowful wisps would escape through her nostrils. But it did not work for now no matter how hard she tried. Now she was suffering in quiet indignation. She badly needed to tell Ms. Fang about the boy, but to tell her now at this very moment would be to cause a scene – and the idea of everyone turning around to look at her and her wet face was just simply too much to bear.

Ms. Fang was looking around at everyone’s face in the class with her bulbous eyes before they landed on Tsunami at the back of the class. Ms. Fang squinted, as if she couldn’t tell if Tsunami was crying.

“Girl,” Ms. Fang said, looking at her pointedly. She got up from her seat and started walking towards her. “Why are you crying, girl?”

This recognition made Tsunami suck in a quick, shaky teary breath. It was time to tell.

“There’s a boy,” she pointed outside the window with a dart of her finger. “Shaking the tree. There’s a nest in the tree. He’s killing the baby birds!”

Then they both looked out the window together – Ms. Fang standing, Tsunami on her two-legged chair. The boy spotted Ms. Fang and ran off without a word. Tsunami couldn’t tell if the nest had fallen onto the floor while seeing out of misty eyes, but her heart was a ship sinking in sorrow.

“I need two prefects,” Ms. Fang commanded.

Two prefect boys stood up – A and A, Aaron and Anson, the twins who loved running teachers’ chores that required getting out of the classroom.

“Go down and check on the nest,” she said. “And see if you can get that boy’s name.”

A and A went out of the class eagerly at a speed just below running (they weren’t allowed to run in school).

Ms. Fang walked back to her desk at the front of the class and rummaged in her handbag. Since all eyes were on the teacher, Tsunami allowed herself some sobs. She sniffled and snorted, when suddenly she saw a tissue paper being handed to her.

It was Ms. Fang. Tsunami took the tissue gratefully as her nose had exceeded its mucus-holding capacity, just like how her chest had exceeded its sorrow-holding capacity.

“Class,” Ms. Fang said in a grave tone. “What the boy did there was very bad. He had fun at the expense of innocent unborn lives.”

Ms. Fang started pacing around regally like a queen departing a most important message.

“We should always respect nature,” she added like a commandment.

“But,” Ms. Fang continued, and turned to Tsunami. Tsunami’s heart stilled. She thought she was going to be reprimanded for leaning back on her chair. Or for failing to tell her earlier, for disturbing the class. For causing a scene. Or perhaps, for keeping the eggs her secret.

“I think Xin Mei’s provided a wonderful example for you all to learn from,” Ms. Fang said gently. “She was brave to try to stop the boy, and the fact that she’s crying shows that she has a big, good, kind, heart.”

Tsunami’s tears stopped and she looked up and met Ms. Fang’s bulbous eyes in surprise. She saw two images of herself reflected in Ms. Fang’s eyes, looking back at her.

“And for that, I think she deserves a round of applause,” Ms. Fang told the class.

Just like that, a magnificent round of applause ensued.

Ms. Fang was clapping as well.

The tears on her face dried up slowly due to all the wind from everyone’s clapping hands.

Tsunami knew that her classmates were only clapping because the teacher told them to. She also knew that if it weren’t for Ms. Fang, none of them would have –could have–helped her. But somehow it all didn’t matter. She had 45 pairs of hands dedicated to her heart.

Tsunami’s breast swelled with something like pride and she felt as if she were hatching out of a shell. Deep down she knew that the nest had fallen. In her mind’s eye she could see the eggs with their shells cracked, watery yellow bleeding out of them before they could morph into feathered flight. But in that moment, everything was covered by the sound of congratulations. So she let the thunderous applause gently rain down on her, with arms outstretched like wings.

Continue reading