Kaitlin Solimine – An Excerpt from “Empire of Glass” (Chapter 1)

Translator’s Note

You never enter Beijing the same way twice. For centuries this was a hidden, forbidden empire: nine gates through which to pass, each with a melliferous name (Gate of Peace, Gate of Security, Gate Facing the Sun), each moat, wall, guard tower knocked down then rebuilt. First the Mongols, the Manchus, then the Boxers and Brits. So many defenses needed to protect the Peaceful Capital that eventually it was renamed Northern Capital—Beijing—for fear of instilling a false sense of quiet.

In the twenty years I’ve lived here, I witnessed hutong alleyways paved over by four-lane highways, a landscape of construction cranes pocking the horizon with hungry, steel arms; my old neighborhood with its elderly inhabitants, once accustomed to shared squat toilets and courtyard kitchen fires, shipped to the suburbs to make way for a Holiday Inn and an office tower with iridescent windows reflecting an endlessly gray, heavy sky.

The world feels drenched in that same impenetrable gray as my taxicab from Beijing international airport reaches suburban Huairou Cemetery. The city around us begs for rain. Along the dirt alleyway to the cemetery gates, a pack of street dogs lazily rise, sniffing their tails. A pair of eyes faces our approaching headlights, briefly golden, briefly human. Hello, old friend, I want to say, only I haven’t met this dog before. There’s just the feeling of having known him for quite some time.

Not far from Huairou Cemetery, the Gobi hovers, China’s “endless sea” of golden sand dunes and failed reforestation: parched, exposed roots and nomadic tribes now cemented to rows of apartment blocks buttressing northern winds. In spring, these winds roll south, roiling the capital’s streets, clogging alleyways with dust, narrowing eyes of bicyclists who tongue grains from their teeth, cursing the season’s turn. In April, snow arrives: fallen catkin blossoms drifting to earth in a city overpopulated with poplars and willows, too many females of the species lending seeds, expectations unmet. And in late May, I land in the city, temperatures climbing past thirty centigrade, old men in tank tops on wooden benches fanning sagging breasts, the sky a dome of heat and haze, encapsulating one of the world’s largest cities, once my favorite in the world.

In my pocket, Baba’s missive from two weeks earlier pulses digital blue:

Come home for Mama’s twentieth memorial.

The first and last text message he ever sent.

I’d replied in Mandarin: You have a mobile phone? 🙂

He didn’t answer. He never understood messaging to be a two-way conversation.

Beyond the gate announcing the cemetery’s Peaceful Garden, parched willows rake thin soil. A concrete wall guards the dead inside: stone steles and a mausoleum for the poorer souls in sealed boxes. Ashes rise from a crematorium to a nondescript sky, quickly lost. I want to tip my head upwards to swallow it all, disappear.

“Menglian!” someone calls from behind the gates as I hand the driver my fare. The stranger uses my Chinese name, the one I give to acquaintances and write on China’s never-ending bureaucratic forms. Baba named me Menglian during my earliest days living with his family, the Wangs: Menglian, or ‘Dream of the Lotus,’ similar to the Chinese name for Marilyn—as in Monroe. I’m not blonde, I said, but Baba laughed and said, “All Americans are blonde.” Only later did he call me “Lao K” after his wife, Li-Ming, decided this was appropriate—“Old K,” the girl named “K” who keeps returning—because it was expected from my teenage years onward I’d always return from my hometown in coastal Maine to this city, one of the world’s most populated, and to the strange Chinese family who first hosted me here.

“Menglian!” the voice repeats.

Rounding the corner, I see a woman wearing silver-rimmed glasses and waving a red glove. She looks vaguely familiar—a scent you pass on the street yielding a feeling but not a name.

“Nice to see you again, Menglian!” Her short hair, the same as Li-Ming’s in her last days, is not a style befitting older women yet she and her friends sport the hairdo like it’s required for Party pension. She’s tall and thin to Li-Ming’s short and squat. Her oblong face is mottled with sunspots. She squeezes my shoulder, inferring we once shared something deep and lasting. I can’t pull the woman’s name from my jetlagged memory; in her dying days, Li-Ming had so many friends, cheery-faced women drifting in and out of the apartment like ants attempting, unsuccessfully, to transport a rotting piece of fruit.

The woman introduces me to a laughing, happy crew of women. They wear blunt, dowdy heels dusty from the walk from bus station to cemetery, long skirts glancing socked ankles, bright colored cardigans (peacock, seafoam, lavender) buttoned to their necks, hair the requisite crop.

“This is Li Xiahua,” she says, pulling me to a tall, pretty lady with plum-lined eyes.

“And Pang Huayang.” Pang: stout with a humped back, dyed black hair, an elbow-shaped chin; someone you know your entire life and only in middle age realize is your best friend.

“Of course you know Mama’s oldest friend, Kang-Lin.” I’m led to a woman with large breasts peeking beneath a tight, too-sheer aqua blouse. The only name I’ve remembered from those early days is Kang-Lin’s—and her face, from photographs—the uncharacteristic freckles dotting her cheeks and nose, the round, rimless glasses guarding a pair of well-kohled eyes. Kang-Lin was Li-Ming’s friend decades earlier, a girl Li-Ming referred to as the “owner of the books”—it was Kang-Lin who gave Li-Ming her beloved Cold Mountain poetry when they were young. Li-Ming never spoke of what had happened to Kang-Lin, but the woman’s re-appearance seems something of a celebration. After Li-Ming’s death Kang-Lin sent my Chinese host mother’s sarira to me in Maine—the Buddhist crystals that form in the cremated remains of only the most devout. Cold Mountain himself left behind sarira. Li-Ming did too, or so I hoped the afternoon Kang-Lin’s package arrived, the envelope’s gritty contents entrenching my finger as it dug deeper, as I wondered how a body so fleshy could turn granular and coarse.

“Nice to finally meet you, Kang-Lin,” I say. She takes my hands in hers, priest-like. The chimney in the distance spews smoke—ashes of a body expired?

Baba, usually on time to pre-arranged meetings, isn’t here to explain Kang-Lin’s return; his tardiness feels like the hollow of an unrung bell. Where is he?

“Your Baba will be here soon,” Kang-Lin says, insinuating she and Baba have recently been in touch.

The plain-faced woman perks up, waves into the distance. “There he is! There’s Wang Guanmiao!”

I follow her finger’s point as Kang-Lin also turns, dropping my hand. Crows bobbing between trash piles on the path to the cemetery look up too, staring down the road to where the suburbs hum and chatter, preoccupied with their forward-looking progress.

Ba, the crows bleat.

Ba, my heart beats.

Ba. Ba. Ba.

I once read crows have the ability to remember a face they saw years earlier. Are these the same crows Baba passes on his annual pilgrimage to his wife’s grave? Do they recognize him? His hair, what’s left of it, parted? His body in the Western-style suit I bought him five years earlier (he’d giggled when the tailor traced his armpits; I’d reveled in this childishness, my generosity)? His feet are crammed into loafers his daughter Xiaofei brought from Hong Kong, recently spiffed and shined. When dressed smartly, he looks like a boy in man’s clothing, never quite grown into the adult he became. He strides, oblivious to the pines above his head, the curious crows bowing in unison. He waves. And waves… It’s taking him too long to reach us.

“Yes! We’re here!” We say.

Waiting. Waiting and waving.

Time takes on a curious rounded feel like the edge of an old coin.

Finally he places a hand on my arm. With the other, he pats down what remains of his hair. He’s an injured bird attempting to fly: all heart, no hop.

“Here,” he says, reaching that same hand into his knapsack and extending a book for us to see. “She told me you were looking for this.”

He hands me a book wrapped in a tattered pink pashmina (the same pashmina I left in his apartment during my Beijing University year) and I don’t need to unwrap the package to know—Li-Ming’s Cold Mountain poems, the collection of eighth century Taoist-Buddhist poetry she wanted to read me during the last weeks of her life and yet we always found ourselves speaking of other things, distracted by a life waning into its final form—

What makes a young man grieve

He grieves to see his hair turn white…

“Now that we’re all here, shall we go?” The short-haired woman gestures at the burial grounds hidden behind lazy willows.

“Quick, quick,” Baba says, leaning so close I smell his lunch—garlicked and soyed—on old man’s breath. He whispers, “Did she visit you today too?”

Before I can reply I haven’t heard Li-Ming’s voice in years, he forces a smile—stained teeth, suntanned cheeks, cracked lips—evidence of a life lived in this thirsty city. He grips my elbow as we follow Kang-Lin’s knowing sashay, the woman’s slender hips hidden beneath folds of a long, black skirt, heels clicking a consistent beat, all of us entering this walled city of bones together.

Confident there will be time for reading later, I tuck the book into my purse, its weight slapping my side, Beijing’s sun shouldering the last touch of dusk.

*

But the book isn’t what I thought. I learn this a few hours after I return to Baba’s apartment in Deshengmen, the six-story building with brown walls scarred by Beijing’s arid seasons, trash chutes with chunks of hardened zhou, dusty bikes rusting in entranceways, abandoned a decade earlier for Xiali sedans that crowd the courtyard.

“Where are Li-Ming’s Cold Mountain poems?” I hold up the book to Baba’s face, peel open the pages that aren’t full of the ancient poems I hoped but of Li-Ming’s scrawl—a journal or notebook. At the kitchen table in the living room where Baba sleeps nightly on a futon, he leans over a warmed bowl of soy milk from breakfast; in this apartment, no meal is too old to reheat, no room holds a single purpose. This is the China of old.

“That’s the book,” he says, nonchalant as a cat.

“No, Li-Ming had a book of Cold Mountain poems. She said one day it would be mine.”

I hold open the spine of the Cold Mountain poetry book whose pages are bizarrely absent, ripped out and discarded, replaced by a blue-lined bijiben notebook—the kind Chinese high school students use for character study. Contained inside are rows of tight, careful calligraphy, penmanship I recognize as Li-Ming’s. On the outer cover, a new title, “Empire of Glass,” is repeatedly scrawled over the smiling hermit face of Cold Mountain—EmpireofGlassEmpireofGlassEmpireofGlass—like a schoolgirl obsessively penning her beloved’s name.

“It has to be here somewhere,” I say, ducking below the bed. I want the poems she promised she’d leave me. I want to read the notes she wrote in the margins, the criticisms she said would one day make sense, the book I couldn’t find after her death no matter how much I searched the apartment shelves full of Xiaofei’s tattered textbooks and mothballed baby clothing.

“Don’t bother,” Baba says. “This is all that’s left.”

*

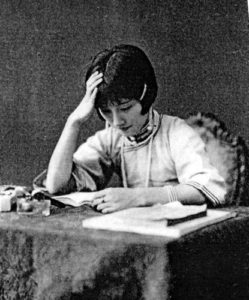

I first met Empire of Glass’s author, Huang Li-Ming, twenty years ago when I was sixteen and she was forty-four. I was an American high school exchange student living with her family in a cluttered apartment in the center of Beijing during an auspicious year according to Chinese superstitions, my 16th (16: one followed by six, 一六, also means “will go smoothly”), and a terribly inauspicious year for her, her 44th (the number four, 四, a homophone for the Chinese word for death). Beijing wasn’t as gray then—yes, the populace wore tans, olives, and navies, and Tiananmen’s bloody stains were only recently painted over, but there was an energy to the wide boulevards filled with bicyclists and yam vendors and smells you hated at first then yearned for decades later when they were replaced by car exhaust and factory run-off from the suburbs. That energy was humanity. Life. Limbs and elbows spurring rusted bikes to the most exciting of newly-formed ventures (black market currency exchanges outside China Construction Bank, stolen factory Patagonia fleeces in Silk Market alleyways, or hamburgers—and free ketchup!—at McDonalds).

There was no better time to be an American teenager in Beijing, bicycling wide willow-lined avenues, getting lost in endless mazes of hutong alleyways still clustered around the city’s heart. When my Mandarin was advanced enough to hold a lengthy conversation, Li-Ming invited me to sit with her on the sundeck after school for what she called her “poetry lessons.” We never actually talked about poetry.

“Do you remember the days you couldn’t tell the difference between a baozi and jiaozi?” she once asked, then launched into a diatribe about the tastiest red bean baozi she discovered in a Tianjin back alley. “Like the Buddha’s touch: the baozi was that good.” She ran her tongue along the memory of sweet paste clinging to her gums.

Another afternoon: “Did you know there’s a particle of physics so small it controls all the energy in the universe?” At the most cellular level as well as the most expansive, she said, science’s knowledge breaks down. “Big and small, equally unknown.” She peeled apart the fingers of Baba’s beloved ficus plants, oblivious to her destruction.

“Fools,” Baba called us every afternoon he returned home from his danwei where he grinded glass for telescopic lenses, carrying bags of wilting lettuce and flaccid carrots from WuMart and smelling like metal—cold and distant. 神经病.

“Did you know there’s a hill in the center of the city so cursed only the bravest go there to die?” This she asked me the afternoon she also told me about the cancer crawling from her breasts to her brain. The same afternoon she told me about her plans on Coal Hill—how I’d help her get there in a few months’ time. How everything would be different once we reached the mountain’s crest, once we read the poems together, able to see everything and nothing.

Our minds are not the same

If they were the same

You would be here?

During each session, the book of Cold Mountain poetry sat on her lap, opened to a page she’d occasionally glimpse, running her fingers over the lines as if they had a shape, but never reading them aloud. She took comfort in the fact I sat with her, and I sat there because I took comfort in the fact she sat with me. Not until much later did I realize the greatest friendships are those with whom we have the easiest ability to sit still together, the people in our lives who don’t question our intentions or why we find ourselves side-by-side on lazy Beijing afternoons with dust caught like a yawn between the sun’s fingers, ficuses scratching our backs, pages open on laps lit so white by the final burst of light, we can’t read the lines.

Li-Ming was impetuous, stubborn, fanciful, and at times, adrift as a spring aspen seed. Her daughter sought in her a distant, loving approval, and her husband, or so I thought at the time, saw her as a companion, that person you forget to question after so many years, a presence critical to your life, but never illuminated as such. Not until I read Li-Ming’s book would the world of that year flip on its head, my involvement in her final days proving I was just one last spoke in a wheel rolling for a long time; despite how much I desired to be the central hub, for Li-Ming, the world was not so carefully defined—was she mentally unstable? A genius? A spiritual scribe? Who was she? I now wonder, lifting my pen from the page and glimpsing a city so full of silver skyscrapers the sky has been made irrelevant….

Had I known of Empire of Glass’s existence, I may never have returned to China after Li-Ming’s death. I may have been too disillusioned to believe China could retain something of the old in the new, that the woman I knew may be there yet, waiting at the top of Coal Hill for me to join her beneath that sickly Scholar Tree, to hand her an ending, close the loop. But I’ll explain more of that later.

For most of its existence, Empire of Glass was hidden beneath the living room’s futon, discovered by Baba when sweeping away decades of dust. Had he still believed in poetry, still heard the beat of his own poetic heart, he may have studied the pages longer—but he merely kicked it under the bed the way he’d nudge a stray Deshengmen cat out of his path. Not until the days drew nearer to his wife’s memorial, when his daughter moved to Hong Kong and I settled in the U.S., did he feel the oppressive loneliness that comes with age, with living too long in one place, the corners of his apartment edging closer, such that eventually he knelt on the concrete, dug deep beneath that futon he once shared with his wife, and cursed the heavens for smacking his head on the wooden frame. “Here you are, old friend,” he said, rubbing the sore bump, but then again, so much of what I’m telling you is already reimagined, reconfigured so convex angles are made concave, mirrors reflecting other mirrors reflecting an uncertain, setting sun.

The ethical challenge of translating Empire of Glass is not lost on me: this strange, hodgepodge book was Li-Ming’s last gift to me and my implication in its narrative makes me an unusual, if suspect, translator. Yet I expect this was carefully orchestrated—Li-Ming would’ve known of my return for her memorial, the agony on the stray dog’s eyes, the lichen climbing the cemetery’s front wall. She expected me to understand her language as well I could, and to one day provide this translation, which has become her last work, this novel. Li-Ming’s Empire of Glass reflects the desires of poet Stephen Dunn: “Every day, if I could, I’d oppose history by altering one detail.” Li-Ming took this directive one step further, altering enough of her life’s details to completely rewrite the world we expected her to leave us.

For Li-Ming, the world we see with our eyes or touch with our fingers is but one dimension. There’s another perspective, one read between letters and shuffled barefoot over the cold dirt of mountain caves while tempered pines shake off spring snow. And this is where we find a circular, ever-coiling link between beginning and end, that and this, other and self, form and formlessness that is the subject of Taoism, Buddhism, and of course, we’d be remiss not to mention here, Li-Ming’s beloved Tang Dynasty poet, Han Shan—or “Cold Mountain.”

If young men grieve growing old, what do old men grieve?

Li-Ming would’ve rewritten Cold Mountain’s verse to assert that old men—and women!—grieve the beginning. Which is why in the end she returned to hers. And although we carried her there on her backs, the load is much lighter now.

“Lao K”

Beijing, China

2016

Continue reading